I have lived on the Outer Banks for close to 40 years now, and while I realize that does not give me native status — or knowledge — I’ve fancied that I’m more than a little aware of the history that has come before us on these shifting islands due to my local profession of writing and publishing about the area. So, when talking with KaeLi Schurr, director of the Outer Banks History Center in Manteo, about an idea for this issue’s feature article, I was momentarily quieted when she said, “How about windmills?” How about windmills, I immediately thought? What windmills? Sure, I knew of the current-day ones, but that wouldn’t exactly an article make.

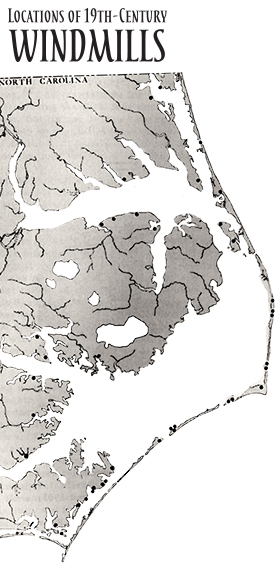

She was talking about the 155 windmills that existed in the North Carolina Coastal Plain from the early 1700s until just past the beginning of the 20th century, 45 of which were along the Outer Banks! I must have looked at her with somewhat absent eyes as I pondered this fact … 45 of these things in our own backyard, from Corolla to Ocracoke, and I had no idea of their history. Yes, this was the story to tell. Surely this would be news to a lot of you readers too.

In our present determination to search out renewable sources of energy (well, determination by some), when we think of windmills our mind image probably goes to the three whirling devices at Jennette’s Pier, the hard-fought-for pillar at Outer Banks Brewing Station (more on those later) or, if you’re a visitor and from a forward-thinking state, a windmill in your city or town. Perhaps, if you’re a Roanoke Islander, you think of the one in the backyard of a home on the north end that pumps water for the owner’s koi pond, the one at Island Farm or the innovative design of the one in the back yard of COA. If we’re observant, we bring to mind the National Park Service’s 70-foot-tall tower at Coquina Beach. Windmills do exist here today, but isn’t it interesting and maybe a little ironic that this stretch of sand that once housed so many of these wind-driven devices is now all but devoid of them by comparison? The landscape and wind that made them logical power-inducers sure hasn’t changed.

In our present determination to search out renewable sources of energy (well, determination by some), when we think of windmills our mind image probably goes to the three whirling devices at Jennette’s Pier, the hard-fought-for pillar at Outer Banks Brewing Station (more on those later) or, if you’re a visitor and from a forward-thinking state, a windmill in your city or town. Perhaps, if you’re a Roanoke Islander, you think of the one in the backyard of a home on the north end that pumps water for the owner’s koi pond, the one at Island Farm or the innovative design of the one in the back yard of COA. If we’re observant, we bring to mind the National Park Service’s 70-foot-tall tower at Coquina Beach. Windmills do exist here today, but isn’t it interesting and maybe a little ironic that this stretch of sand that once housed so many of these wind-driven devices is now all but devoid of them by comparison? The landscape and wind that made them logical power-inducers sure hasn’t changed.

You see, these flat islands that are not adorned with particularly tall trees (again, by comparison) were the ideal locations for wind-driven machinery. Before our society began to rely on fossil fuels to power our machines, wind was a force that was fairly dependable, at least here. Water would have been too, but we were flat, and you need changes in elevation for water power to work. In addition, the skills of Outer Banks craftspeople, the boat builders and sail makers, fit like interacting cogs with those needed to build a functioning – and balanced – windmill.

From the early 1700s until just past the beginning of the 20th century, there were 45 windmills along the Outer Banks.

The earliest known windmill to be built on the Outer Banks, according to research done by North Carolina historian and writer Ben Dixon MacNeill, was in Avon — more poetically known then as Kinnakeet — in 1723. Another one that has definitely been documented was at a location in nearby Pasquotank County called Old Windmill Point (locals or long-time visitors, notice any connections here?) in 1758. When you look at the map and see all the dots along our shores where these structures stood, it’s clear that windmills had gained in importance and numbers by the mid-19th century.

Which, if you’re a curious reader, might make you even more so. Who among us has seen amber waves of grain or tall stands of corn growing along our sand-prevalent ground? Right? But what we did have/do have in abundance was seafood, and this aqua-money provided means of trade on the mainland for needed grain. Boats would haul nets of our bounty over in exchange for bags of their bounty, and back the Bankers would come to the mills dotted all along the coastline. It worked pretty well.

It worked pretty well until it didn’t, and that happened during storms when windmills would either be damaged or destroyed or whir too quickly to grind the desired consistency of meal. It also happened when wind was low for any number of days, which even here on these wind-swept shores did happen. Accounts of old-timers in articles such as “When Windmills Whirled on the Tar Heel Coast,” written by noted historian Tucker Littleton for The State magazine in 1980, tell of how locals would pray for wind during those times just as they would for rain during dry periods.

But during normally windy days, of which we have a preponderance, these wooden windmills, often made of salvaged materials, were modern timesavers. No more mortar and pestle drudgery for that coveted cornbread.

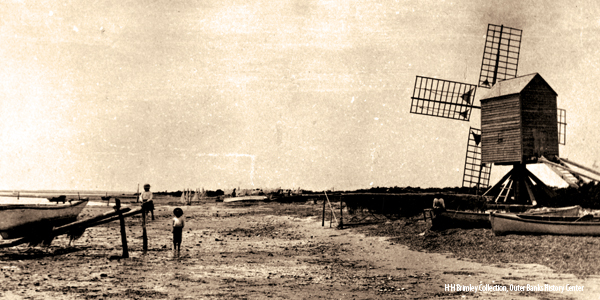

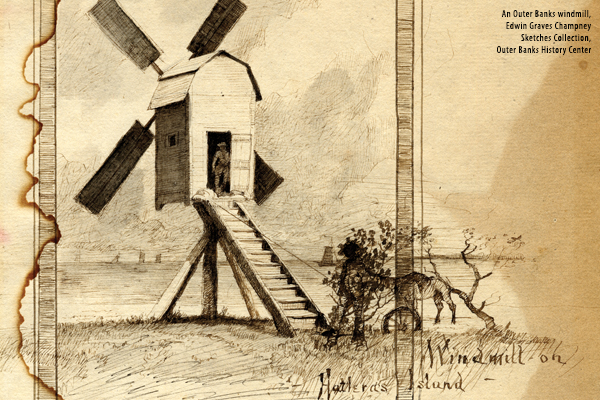

And what of these wooden structures? When you picture an Outer Banks windmill, do you see a Dutch landscape scene? If so, though understandable, you’d be wrong. The mills built here were called interchangeably post mills or German mills, not because they originated from that country, however, just as the Dutch design is not a namesake either. Historians (R. Wailes in The English Windmill and R.J Forbes in Studies in Ancient Technology) tell us that the style of post mills built here was first noted in England in the 12th century! Other areas of the early colonies in this country tended to use the Dutch mill design (a.k.a. tower mills, often built of brick with a wooden cap that turned). Leave it to us Outer Bankers to stick to the old ways! But, as you’d expect, there were reasons to do so.

The post mills were wooden structures that were mounted on a middle post. A ladder provided access to the housing, and a long tail pole that protruded from the structure and was attached to a wheel on the ground that went around a metal or stone track allowed the miller to move the entire windmill around to catch the wind. Pretty ingenious, don’t you think? These mills were anywhere from 20 to 40 feet tall, and the wind sails were usually around 20 feet long. The sails could be adjusted for wind speed (hence why they were short enough to be reached from the ground with a little boost). Top efficiency reached an average of 14 horsepower. Since these mills were wooden and only attached to the ground by way of the center post, they were moveable, unlike the tower mills. Thus, if a miller wanted to sell his mill, he didn’t have to lose his land in the transaction. It’s unlikely, however, that local windmills were moved much since either storms or rot (they were mostly built of pine) took many of them down on a regular basis. In fact, a massive hurricane in 1898, during which sustained wind speed reached 155 mph, destroyed most of them here.

You can see what a post mill looks like at Island Farm on Roanoke Island; they moved the one that was built as an exact replica of a local 19th-century mill and that was on display in Nags Head from late fall of 1980 until a few years back. The story of this windmill is worth telling and was related to me by John Wilson, one of the owners of Island Farm and a man who has worked his entire adult life to maintain the simple and beautiful heritage of Roanoke Island. He explained that the National Park Service was interested in building a reproduction of a post mill windmill that would have existed on the island. An English craftsman was hired to come up with the plans. But before the windmill could be built, changes in leadership at the state level meant changes in funding for the project. But a woman who had been a part of the plan, Lynanne Wescott, was too enamored with the thought of bringing this picturesque piece of history back to life on these shores to let it drop, so she used her own money to have it built. Originally, it stood as a kind of moving marketing sign to attract people to her gift shop, which stood on a piece of the land where the Nags Head Event Site is today. Later, it served the same purpose for several restaurants, one of which was called Windmill Point. When the town of Nags Head purchased the acreage for their event site, John and his partners at their Outer Banks Conservationist nonprofit (they also restored the keepers’ quarters at Currituck Lighthouse and manage that property) were quick to obtain the reproduction mill and have it moved to Island Farm.

This farm is so worth a visit if you want to understand and visualize the Outer Banks of the several-centuries-old era (and kids, who have no desire for the history of it all, have a fantastic time going back in time with games, hayrides and other fun). You’ll experience a farm much as it was in the mid-1800s with the family home, barn, out buildings and pastures with sheep, ox, cattle and horses. Though the map included in this article shows only two windmills on Roanoke Island, the article by Littleton noted that there were four here, and John, whose family has been here for many generations, says that there were probably more than that at various times. One of them was actually located at the Etheridge family farm — the farm that has been brought back to life as Island Farm — though then, in the mid-1700s, the farm encompassed much of the land on the north end of the island, so the windmill was situated near to the present day Elizabethan Gardens. Island Farm is living history, and part of the intrigue of the place is in understanding the necessary, but thought-provoking to the modern visitor, self-sufficiency of the islanders in past eras. The land provided food and grazing ground; the wind produced a power plant that provided ground meal for cooking and baking; the water provided fish for eating … all without fossil fuel. Within a few years, the windmill you see at the farm will, once again, be grinding grain. Though they’ve had to wait for more than two years, John and his partners have finally been able to contract with Dean Reudich, North Carolina’s preeminent restoration craftsman, to bring the windmill back to working order. He will work only by hand, just as the builders of centuries back did.

So, speaking of power plants…. By means of some fabulous quirk of nature, the local wind hasn’t changed character for centuries. It still blows strong and mostly constant. These islands are still flat, and the trees that grow here haven’t morphed into giant redwoods. The Outer Banks could be — and many think should be — the ideal location for wind-powered energy. Some forward-thinking locals have put their aligned beliefs into action. The owners of the Outer Banks Brewing Station kept at the permitting process for five years, determined to place a tall wind turbine on their property. Today, the modern-day windmill saves them up to $250 per month on their power bill. (For more information on them and their efforts, see their article in this issue.) Jennette’s Pier, part of the North Carolina aquarium system, sports three spiraling turbines, thanks to the efforts of Senator Marc Basnight, who was a leader in encouraging this pollution-free energy source while he as in the state senate. Scientists at the local Coastal Studies Institute are researching the future of wind and wave energy here. Classes are taught at the local community college on installing our modern windmills as well as solar panels. We’re moving forward.

But I wish we could move back in time to when windmills dotted our beloved Outer Banks like pearls on a necklace, to when, if you traveled as the crow flies from Corolla to Ocracoke, you’d see an average of one every 2 miles. That’s what I want. It’s not tilting at windmills … it’s not fighting a battle that can’t be won. And, isn’t it just like the Outer Banks to look to our history for our future, as we’ve done with everything from English civilization to powered flight (which works, of course, in part with the lift created by wind speed)? If our local ancestors existed in a world of wind power, perhaps we can learn from history … and repeat it. Certainly, the self-sufficiency would mirror the determined Banker throughout the last 300 years. Plus, I have to agree with John when he said, “I just think they’re beautiful. All of them.”

Beth Storie first came to the Outer Banks for the summer of 1976. She fell in love with the area and returned for good three years later. She and her husband published the national guidebook series, The Insiders' Guides, for more than 20 years and now are building OneBoat guides into another national brand. After spending time in many dozens of cities around the country, she absolutely believes that her hometown of Manteo is the best place on earth, especially when her two children, six cats and one dog are there too.

Beth Storie first came to the Outer Banks for the summer of 1976. She fell in love with the area and returned for good three years later. She and her husband published the national guidebook series, The Insiders' Guides, for more than 20 years and now are building OneBoat guides into another national brand. After spending time in many dozens of cities around the country, she absolutely believes that her hometown of Manteo is the best place on earth, especially when her two children, six cats and one dog are there too.