Listen To This Article

Here on the barrier islands where the landscape is defined more by water than by land, bridges are a vital part of life. Of course they are necessary physical conveniences that help us get to and from the mainland and between the islands with ease. But the Outer Banks bridges are more than just concrete and steel structures spanning bodies of water.

Here, bridges are connections and lifelines. They are our link to the outside world, easing the arrival of visitors and delivery of goods so that we can all enjoy living and playing here. They connect our residents, villages and towns, joining the Outer Banks as one big community rather than several isolated islands. They are salvations in storms and emergencies, helping us quickly evacuate or rush people to medical services.

The Outer Banks is linked to the mainland by three major bridges (Umstead, Virginia Dare, Wright Memorial), and the islands themselves are linked by three large bridges (Baum, Basnight, Jug Handle) and several smaller bridges (the Little Bridge on the Manteo/Nags Head Causeway, the two that link Big Colington Island and Little Colington Island to Kill Devil Hills and more).

From the longest bridge in North Carolina, the 5-mile Virginia Dare Bridge linking Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, to the tiny Cora Mae Basnight Bridge spanning Shallowbag Bay from Downtown Manteo to Ice Plant Island (and from which local kids jump as a rite of passage), these bridges make our lives easier. And some of the bridges, like the ornate, c. 1922 bridge that’s part of the Whalehead complex in Historic Corolla Park (and can be seen on our cover), just make life more scenic and beautiful. It’s functional as it spans the canal, but it’s also one of the most photographed sites on the Outer Banks.

Bridges make our lives easier, but it was not always this way. Generations before us were taking slow ferries and mailboats across the sounds and Oregon Inlet and paddling, sailing or motoring boats across all the little creeks and canals. Keep reading to learn about how and when the first bridges were established here and how they contributed to the growth and prosperity of the Outer Banks.

The First Bridges

Prior to the 1920s the islands weren’t just remote, they were truly isolated. People got between the islands and to and from the mainland by boat, and it wasn’t always quick or easy. Sailboats then motorboats, mailboats and small ferries shuttled people across the water. A few visitors came to Nags Head via boat in the summer, but for the most part the barrier islands were sparsely populated, and in the early 1920s, Dare County’s economy, mainly dependent on fishing, maritime traffic and the Coast Guard, was on the decline.

In 1924 Washington F. Baum of Manteo became chairman of the Dare County Board of Commissioners and began a campaign for Dare County’s first bridge. Businessmen from the north were buying up land on the beach and had convinced Baum that Dare County had a bright future because of its beaches – if only there were bridges to reach them.

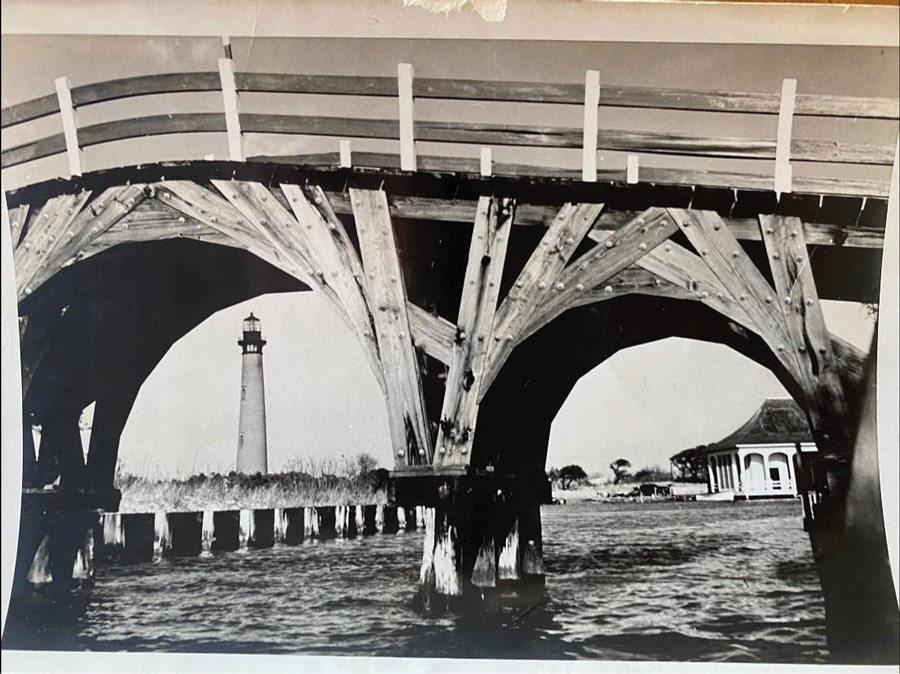

When the state refused to help build a bridge to Nags Head, Baum succeeded in getting a private wooden drawbridge built from Roanoke Island to Nags Head. They saved a good deal of money on the project by using an old 12-foot railroad draw span that had been abandoned by Dare Lumber Company at Milltail Creek on the mainland. The bridge opened to traffic in 1928, with a toll charge of $1 per car.

At the same time, a group of Elizabeth City businessmen were forming the Wright Memorial Bridge Company. They had invested in land north of Kitty Hawk and needed a way to access it besides the small ferry from Point Harbor to Kitty Hawk. They built the second bridge to the island, a 3-mile-long structure across Currituck Sound, in 1930. Made entirely of wood, the bridge featured an archway at the Kitty Hawk end that read Dare County at the top, 1584 Birthplace of a Nation on the left and 1903 Birthplace of Aviation on the right. The toll to cross was $1.

At the eastern terminus of both of these bridges were sand tracks leading toward the beach, which made travel on the island difficult. But it wasn’t long until the state constructed the paved 18-mile N.C. Highway 12 to link the two toll bridges. In a few years, the State of North Carolina took over the two private bridges crossing Roanoke and Currituck sounds.

With easier accessibility, tourism began to thrive on the northern Outer Banks. Wright Brothers National Memorial, Fort Raleigh and The Lost Colony were established, and the idea for Cape Hatteras National Seashore began. Restaurants, shops and hotels opened to accommodate the visitors.

Still, it wasn’t exactly a quick trip to the Outer Banks. In the early 1950s, coming to the Outer Banks from the North Carolina mainland required two ferry trips: first, over the Alligator River and then over Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island. To get to Hatteras, there was another ferry. The ferries created bottlenecks and delays for travelers.

It wasn’t until 1955 that a bridge was built to span Croatan Sound from the mainland to Roanoke Island. The William B. Umstead Bridge, a 2.7-mile span from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, was built in 1955 and named for a former U.S. Senator who served as governor of North Carolina from 1953 to 1954.

The two-lane swing bridge over Alligator River was built in 1962. Still in use today, it stops vehicular traffic to swing open periodically and allow the passage of maritime traffic. Its official name is the

Lindsay C. Warren Bridge, but everyone calls it the Alligator River bridge. Warren was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1925 to 1940. (The 62-year-old bridge is set to be replaced with a high-rise bridge in 2025.)

The wooden bridge that Baum had built from Roanoke Island to Nags Head wasn’t replaced until 1962. The new bridge was officially named the Washington Baum Bridge to honor his early vision of the growth of the Outer Banks. The 1962 bridge was replaced in 1994 and still has the same moniker.

The original Wright Memorial Bridge to Kitty Hawk was replaced in 1966 with a more modern concrete bridge. By 1995 the bridge could not accommodate all the people rushing to the Outer Banks, so the state added a parallel concrete bridge to alleviate traffic buildups. This new bridge became the westbound bridge. The 1966 eastbound bridge was replaced in 1997.

Meanwhile, up until the early 2000s, access to the Outer Banks from the North Carolina mainland was still over the Umstead Bridge, which required slow travel through the quiet Manns Harbor community and the north end of Roanoke Island and Manteo. In 2002, the State of North Carolina opened a bridge across Croatan Sound to supplement the Umstead Bridge and bypass Manteo. The resulting 5.1-mile, four-lane Virginia Dare Bridge is the longest bridge in North Carolina. It took three years to build and is designed to last 100 years. It was named for the first English child born in the Americas in August 1587.

Bringing the People to Hatteras Island

By the 1950s, the hard-surface Highway 12 had been built all the way from Nags Head to Ocracoke village, linked by two ferries crossing Oregon and Hatteras inlets. Cape Hatteras National Seashore opened in 1953 and was drawing hordes of visitors. The island had attractions, hotels and restaurants, and people were flocking to enjoy its pristine natural beauty, but the private ferry to Hatteras Island could not keep up with demand.

Captain Toby Tillet had provided ferry service to Hatteras Island since 1924. Launching with just a few cars on the back of a barge, Tillet eventually expanded his ferry to accommodate up to 14 cars per crossing. In 1950 he sold his ferry service to NCDOT, which continued making daily shuttles across the inlet in the years to come.

But in summer, the wait for the ferry on either side of the inlet would stretch for miles down Highway 12. Traffic congestion was so bad that the park service set up a makeshift camping area in the parking lot at the Coquina Beach Day Use Area to accommodate folks who had to wait overnight for a ride across the inlet. Ferries could only carry 2,000 people a day, not nearly enough spaces for everyone who wanted to go.

North Carolina Congressman Herbert C. Bonner, who had pushed for the establishment of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, helped make the deal to get a bridge across Oregon Inlet. The 2.7-mile bridge, named for Bonner, opened in 1963, greatly easing access to Hatteras Island.

When complete, this bridge welcomed a new era of tourism to Hatteras Island. Visitation increased to the point that the bridge was carrying nearly 2 million cars per year. But storms, erosion in the volatile inlet and the high traffic numbers were making the bridge unsafe by the late 1980s. The state spent nearly $50 million repairing and protecting the Bonner Bridge and N.C. Highway 12 after storms. In October 1990, a dredge collided with the bridge during a storm, causing severe damage to several of the spans, shutting down vehicular access to the island for weeks while the bridge was repaired. The accident illustrated how vital the bridge had become on the Outer Banks.

The Bonner Bridge was due for replacement in the early 1990s, but for nearly two decades the state and environmental agencies disagreed about replacement of the bridge. By then the safety rating of the bridge was 4 out of 100. Finally, construction on a new bridge over Oregon Inlet was begun in 2016. The new bridge opened on February 25, 2019, and was named the Marc Basnight Bridge in honor of a much-loved Dare County resident who served as North Carolina State Senator from 1985 to 2011. It’s the first bridge in the state built from stainless reinforcing steel, and in addition the new bridge’s longer, deeper pilings in the inlet’s floor are built to keep sand from washing away from around the piles. It’s said this design should give the bridge a longer lifespan.

The second bridge you reach on the long stretch of Highway 12 on Hatteras Island is the Captain Richard Etheridge Bridge. The need for this bridge was caused by Hurricane Irene in 2011. Irene was a category 1 storm that caused catastrophic 10 -to 12-foot storm surge from Avon through northern Hatteras Island. Irene cut two inlets on Pea Island, closing N.C. 12 for months and creating the need for a two-hour-long ferry ride from Rodanthe to Stumpy Point for seven weeks.

NCDOT created a temporary bridge that locals called the Lego Bridge to span one of the inlets, which locals were calling New New Inlet or Irene’s Inlet. The inlet has since closed, but since the area is inlet prone, in 2017 NCDOT replaced the Lego Bridge with a permanent structure. It’s a short bridge, only 2,350 feet, and is named for a local U.S. Life-Saving Service hero named Capt. Richard Etheridge. The keeper at Pea Island Life-Saving Station, he was the first African-American station keeper in that service, and he and his crew saved hundreds of lives.

The third and final bridge on Hatteras Island is the Outer Banks’ newest bridge. The 2.4-mile Jug Handle Bridge, also known as the Rodanthe Bridge, was begun in 2018 and opened in the spring of 2022. This bridge was necessary because of constant erosion and overwash on N.C. Highway 12 on the north end of Rodanthe. The bridge begins at the south end of Pea Island and bypasses northern Rodanthe, Mirlo Beach and the S Curves, dropping vehicles off at a roundabout in Rodanthe.

Maybe One Day

The only other Outer Banks bridge on N.C. DOT’s radar at this point is the controversial Mid-Currituck Bridge. The 4.7-mile proposed bridge would span Currituck Sound from the sleepy village of Aydlett on mainland Currituck to the massively popular vacation resort town of Corolla. This would alleviate major summer traffic backups on the Wright Memorial Bridge and on N.C. 12 through Southern Shores, Duck and Corolla. It would be good for traffic and hurricane evacuation, but opponents say it will bring too much change to Aydlett, open up the flood gates for too much development in Corolla and pose an environmental threat to Currituck Sound. The overall 7-mile proposed project includes roadway, a two-lane toll bridge over the sound and a second two-lane bridge spanning Maple Swamp to connect U.S. 168 to Aydlett. The $500 million project is tied up in legal hearings and has no scheduled start date.

The next time you drive on an Outer Banks bridge, think of it as more than just a means to cross water. Think of the way these bridges link islands with the world, the communities with one another and all of the people with their favorite places. And, as we know you will, appreciate the unforgettable views they provide. Roll down the windows. Breathe in the air, enjoy the jolly bounce of your tires over the joists. Sigh in relief as you cross the Wright Memorial Bridge, getting ever closer to the ocean. Feel your heart surge as you sweep over the high arc of the Basnight Bridge, taking in the narrowness of this sandbar. Be glad when you get stopped by the Alligator River swing bridge, giving you the opportunity to get out of the car and peer over the railing into the water below.

Happy travels!

Molly Harrison is managing editor at OneBoat, publisher of OuterBanksThisWeek.com. She moved to Nags Head in 1994 and since then has made her living writing articles and creating publications about the people, places and culture of the Outer Banks.

Molly Harrison is managing editor at OneBoat, publisher of OuterBanksThisWeek.com. She moved to Nags Head in 1994 and since then has made her living writing articles and creating publications about the people, places and culture of the Outer Banks.