It’s fitting to title an article about how the waterfront town of Manteo was remade with a quote from Andy Griffith, “Come sit on our front porch; let me tell you of the dreams we keep.” On the floor of the legislature in the early 1980s, as the narrator of a slideshow of that name showing how transformation could happen in a small, waterfront Outer Banks town, Andy was lending his stature and fame to encourage the powers that be in Raleigh to see the vision of what Manteo could become. He spoke of a town he loved, where he owned a home, where his career had begun. He asked lawmakers to consider what’s worthy of preserving, of revitalizing: the sacred places that have held history, families, culture, a way of life. It worked, as is perfectly clear when you wander through the streets and along the boardwalk of this beautiful little coastal town. But Andy’s support, as important as it was, added to an effort already begun, or at least envisioned, by local son John Wilson, an historic architect, to not just create a nice-looking waterfront area but to also re-envision a town and what it could contain.

The vision was for Manteo to become a fitting place for a 400th celebration of the English attempts at colonization in this New World, attempts that had begun in 1584 through voyages and explorations. And, after the celebrating was finished, Manteo would become a center for cultural and performing arts while melding into a vibrant retail and residential hub. Now, with only a scant three years to transform the town into a place that would welcome royalty and dignitaries, there was work to be done. A project of this size would require local, state, federal and private funding. But, more than that, it would require a belief shared by many that a plan such as this was doable – a steadfastness in the understanding that what we deeply believe, we manifest.

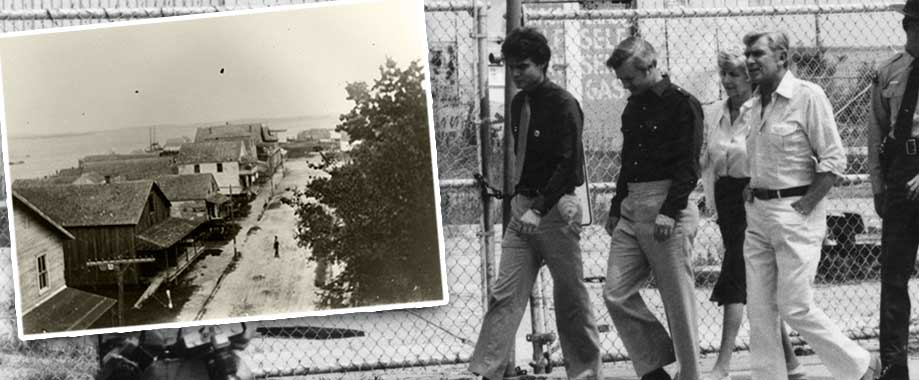

Left: Looking south on Water Street (now Queen Elizabeth Street) in the early 1900s. The smaller building in the middle is about where Poor Richard’s is today. Straight ahead, you would now be looking at the Roanoke Marshes Lighthouse. Above: Mayor John Wilson, Gov. Jim Hunt, Geneva Warren of the governor’s office and Andy Griffith stroll the then-dilapidated waterfront of Manteo, talking about revitalization plans.

I wasn’t in the legislature that day, but I did already live in Manteo when John Wilson was elected mayor in the fall of 1979. I had just graduated from UNC-CH in May and had come back to the Outer Banks for only the summer (or so I thought). But my first impression of this little town had happened the summer of ’76 when I worked in Nags Head after freshman year. Having a waitress job and being on my feet a lot, I decided I wanted a pair of support hose. In those days, there really wasn’t anywhere on the beach to buy such an item. That, as explained to me by my boss, required a trip to Manteo. So, over we came to Davis’s Everything to Wear. To say that I was put off by the town might be too sweetly said. I remember the waterfront area with its unsightly oil tanks, the big, round treatment plant where the lighthouse now sits, the disjointed and old-timey buildings, the zagged hunks of cement on the water’s edge where, I was certain, millions of water moccasins sat waiting. It wasn’t pretty, folks. And, yet.

And, yet, there was something there that, despite what was then the opposite of revitalization, sent out forces that pulled me in. The people were different here than over on the beach. It felt connected in a way that Nags Head didn’t then. It had lovely old houses and a church chime that played music in the afternoon. Obviously, I’m stating an experience that struck an 18 year old on a skin-deep level on a single summer afternoon that John and other champions of the town knew to their bones based on a lifetime in the town: There was something worthwhile to reveal here, and it contained dreams and vision … and it would take a ton of courage and perseverance to bring it forth.

Left Photos: Roanoke Marshes Lighthouse was dedicated in September 2004 and now graces the waterside entrance into Shallowbag Bay. It sits on the platform that once held the town’s sewage treatment plant. Right photos: Top Right Photo: Elizabeth II being built during 1983 on the Manteo waterfront. Bottom Right Photo: The Elizabeth II is the state’s only moveable historic site, helping to tell the story of England’s attempts at colonization on Roanoke Island from 1584-1587.

John and a team of fellow visionaries that included a newly elected board of commissioners, Andy and, eventually, players on the state level such as then Governor Hunt and Senate President Pro Tem Marc Basnight, went to work. They enlisted the help of graduate students from John’s undergraduate alma mater, NC State School of Design, to help townspeople clarify what they wanted in their town. Maintaining the neighborly feel of the town was hugely important. Manteo folk, as well as John and the other leaders, wanted to revitalize a town that considered the needs and wants of locals as well as those of the visitors they knew would come. “If you build it, they will come” was, perhaps, first manifested in Manteo before the popular movie, Field of Dreams. (And, isn’t it just a lovely coincidence that both considered the dreams that maintain us just as potently as the buildings that house those dreams.)

But, amidst the excitement and vision that many felt, as buildings began to be demolished and a new bridge was constructed to connect the waterfront to what is now Roanoke Island Festival Park that blocked easy access for some types of boats, a tenor of fear and resistance began to be heard through the town’s grapevine. Some people feared all this gussying up was for the wrong reason – the town had always been good enough for locals, was a common comment. And what kind of change might come to this place if it was overrun by tourists? Maybe a town that had contained the dreams of its residents for so long shouldn’t be made into something new. Would the essence of the town be lost?

Truth be told, at the point this revitalization began, it could be argued that the essence of the town was already gone, or was at least cruelly waning. What had been a vital waterfront area that served as the government hub of the county and as a community retail center (from the late 1800s to the mid 1950s) with more than 80 businesses had dwindled to only seven businesses in 1976. There wasn’t much reason to come to the waterfront area. Most of Manteo’s commerce had moved out to Highway 64, and the ever-growing popularity of the Nags Head area as a summer vacation haven had begun to take any leftover attention away from the first incorporated town in Dare County. It seemed, in some ways, that the choice was between letting the town all but die or going for it. We all know what choice was made.

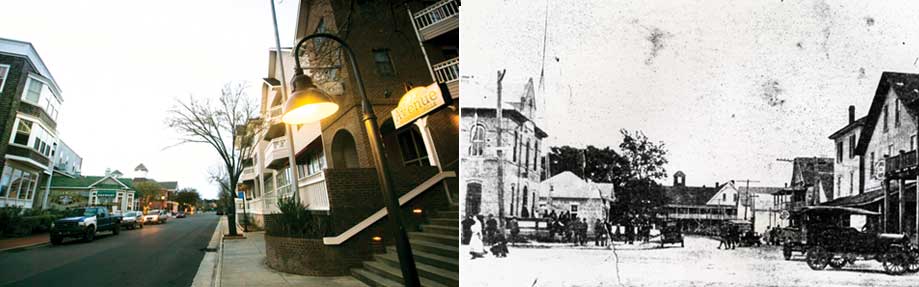

Left: Looking south on Queen Elizabeth Street today you see a town full of shops and residences. The Centennial Court, with its shops and apartments, is on the far left next door to the Lost Colony Brewery and Café. Farther south is the old Dare County Courthouse that, today, is the home to the Dare County Arts Council. On the right of the photo is the Waterfront complex with shops and restaurants on the first floor and condos above. Right: Manteo was the county seat and the center of activity for retail, court cases, shipping and any official business. This view, taken in the early 1900s of what was then called Water Street but now is Queen Elizabeth Street, is looking north.

So, despite some naysayers, or even those who were simply withholding judgment, work continued. As described in Angel Ellis Khoury’s book, Manteo, A Roanoke Island Town, an absolutely wondrous compendium of the town’s history, the Village Plan was “… the public purchase of seventeen privately owned parcels to create three major development sites to include an inn, shops and residences; the rehabilitation of existing buildings; the demolition of others; the acquisition of privately owned land for the creation of a waterfront pubic park commemorating the work of boat builder George Washington Creef; construction of public boardwalks and docks along the perimeter of the waterfront; acquisition of Ice Plant Island across from the Manteo waterfront; construction of a bridge across Dough’s Creek; the cutting of a canal to provide boats access to the sound once the bridge was built; construction of a representative sixteenth-century ship as part of America’s 400th Anniversary Celebration; dredging a channel in Roanoke Sound for the passage of the Elizabeth II and to increase traffic from the Intracoastal Waterway; construction of a boatbuilding center; creation of living history exhibits and programs on Ice Plant Island; and the creation and continuing enhancement of a landscaped corridor through Roanoke Island, linking historic sites.

Take a gander at how many of these items on the Village Plan were accomplished. Every single one. That list wasn’t written in retrospect. It’s a testament to vision and planning and perseverance and to a shared prosperity.

And, on a hot July day in 1984, it was already time for the 400th Celebration. Walter Cronkite was an honored guest and speaker, arriving for the festivities leading a flotilla that glided past Elizabeth II. Her Royal Highness Princess Anne walked along the newly constructed waterfront boardwalk that bordered retail buildings still to be completed and some lots waiting for what was to come. Still, the townspeople turned out with giant smiles and excitement to welcome the thousands who came to celebrate. I remember wearing an Elizabethan era-inspired outfit to sell a publication we had created for the event. There was a buzz in the air. Something was happening in our little town, and it wasn’t only that day of celebration.

From 1980 to 1986, more than $26 million was raised to support the revitalization. Others, clearly, saw the rising of Manteo and decided to play a part. Later in 1984, the Waterfront building was opened with its retail space on the bottom floor and condos on the top two. The Elizabeth II, which was built in downtown Manteo and launched in November of 1983, began touring North Carolina’s coastal towns as the state’s only moveable historic site, helping to tell the story of the first attempt at English colonization in the New World. The Tranquil House Inn opened in 1988. In 1994, Senator Basnight helped establish the Roanoke Island Commission, whose purpose was to create a state historic site – today’s Roanoke Island Festival Park, which debuted in 1998 with its amphitheater, gallery, interactive museum, history archives (now the independent History Center) shop settlement site and Indian town. In 1999, the old post office, located across the street from the Tranquil House Inn, was demolished, and Magnolia Marketplace was built as a space for crafters and artists to create, show and sell their wares. Centennial Court, located next to Lost Colony Brewery and Café, opened in 1999, and The Phoenix Shops, located perpendicular to the Pioneer Theater, were built in 2000. Both added to the retail options and brought more people into town to live in the apartments located above the shops. In 2004, a renovated Roanoke Marshes Lighthouse took the place of the old treatment plant that sat at the end of a pier on the waterfront.

Along the way, old buildings have been transformed into popular restaurants such as Lost Colony Brewery and Café, Poor Richard’s, Hungry Pelican and Ortega’z. A waterfront playground, located approximately where two big oil tanks used to stand in the mid-70s, was dedicated in 2014 to provide a place for both local and visiting children to play. Ice cream shops, a skate park, a maritime museum (on the site where Elizabeth II was built), a book store, jewelry and clothing shops, antiques and more now mirror a time when the town was vibrant with activity. The boardwalk has been extended to include strolling access to the Marshes Light community that, thanks to careful planning by some of the same people responsible for the town’s revitalization, looks and feels like it belongs in this historic town.

Because of Manteo’s comeback, thousands of visitors discover the town every year. Some come to see The Lost Colony, this country’s longest-running outdoor drama, or to visit the Elizabethan Gardens, established in the 1950s, and take part in the many events that occur there. But plenty of them now come for the town. Most never know the transformation they’re seeing. They only experience a waterfront community that seems to have just the right combination of localness and all the things they want as a visitor. They see lovingly restored island homes, walkable streets, restaurants, shops, galleries, attractions, kayakers and paddleboarders, a marina filled with boats of all sizes, art shows with tents that dot the water’s edge, live music festivals amplified by water and wind. If there’re here at a lucky time, they blend into the town’s homecoming or Christmas parades, a holiday celebration, one of the many arts-related events put on by the Arts Council that now inhabits the old county courthouse, a Dare Day celebration in June or a 4th of July event.

And, where do all these events take place or pass through? Yes … through the streets of a small, waterfront Outer Banks town that could have faded into nothingness.

So many nights, at that magnificent twilight time, I stop my walk right in front of the small net house that’s built on the town’s boardwalk. In front of me is a scene that will always be one of my most cherished, no matter how many places of beauty I catalog in my life. There, against a vast sky, is a panorama of a town that is full of life. As I look from left to right, I see several beautiful, historic homes, the Maritime Museum, the grassy and tree-shaded park beside it, softly lit shops in the background, small sailboats in their moorings, the park with the happy sounds of children, the lighthouse blinking its welcome, the Elizabeth II reflecting in Shallowbag Bay’s water, a weather tower that signals the day’s forecast with colorful flags, a waterfront street that connects businesses, diners sitting outside taking in the scene. And I swear it’s true: I always say a silent prayer of thanks to the wise souls who saw this beauty long before it actually existed and created it for the rest of us to experience.

Beth Storie first came to the Outer Banks for the summer of 1976. She fell in love with the area and returned for good three years later. She and her husband published the national guidebook series, The Insiders' Guides, for more than 20 years and now are building OneBoat guides into another national brand. After spending time in many dozens of cities around the country, she absolutely believes that her hometown of Manteo is the best place on earth, especially when her two children, six cats and one dog are there too.

Beth Storie first came to the Outer Banks for the summer of 1976. She fell in love with the area and returned for good three years later. She and her husband published the national guidebook series, The Insiders' Guides, for more than 20 years and now are building OneBoat guides into another national brand. After spending time in many dozens of cities around the country, she absolutely believes that her hometown of Manteo is the best place on earth, especially when her two children, six cats and one dog are there too.