Coming soon, a new museum in Corolla will tell the story of Currituck’s legendary boat builders. Surrounded by sound and ocean waters and interlaced with rivers and creeks, Currituck County is defined by water. And where you have water, you have boats. Whether for work, recreation or transportation, boats are an integral part of life in Currituck County, certainly today, but even more so in previous generations.

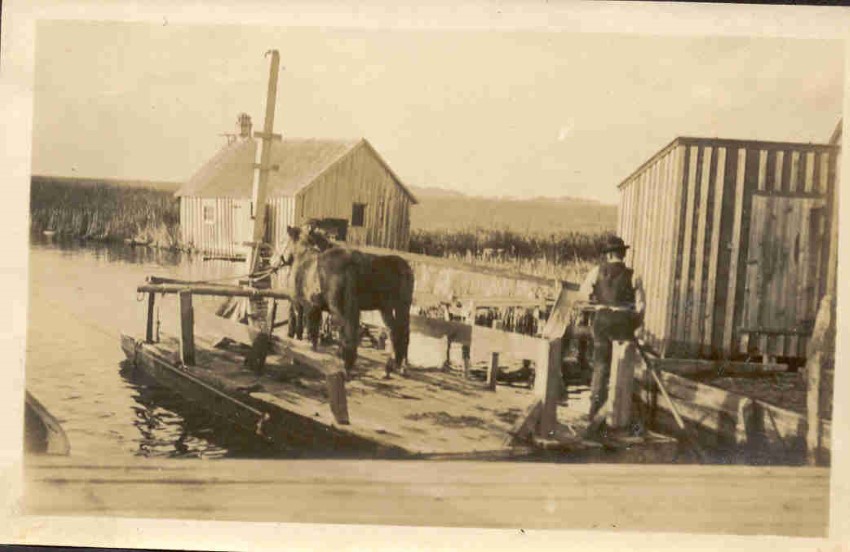

Before the days of slick, mass-produced fiberglass hulls and outboard motors, the vernacular watercraft in Currituck County were simple, locally handcrafted wooden boats and skiffs with heavy inboard motors. Boats such as these were a major part of the Currituck economy for more than 100 years. Native Currituck watermen like Pat O’Neal, Blanton Saunders, Joe Hayman, Oscar Roberts and Billy Corbell built boats for themselves and their neighbors, designing them based on their knowledge of the shallow, choppy Currituck Sound and for the needs of the local people: fishing the sounds, carrying duck hunters to blinds, transporting gear and goods, traveling from the mainland to the sound islands or Outer Banks. These were utilitarian workboats, the pickup trucks of the water, built for the ways of life in the farming, fishing and hunting communities.

The old-time builders probably didn’t consider themselves craftsmen, but they were. Their boats are widely admired for being not only functional but also aesthetically pleasing, with clean lines and perfect proportions.

“The older builders had a conceptual mind just like an artist,” says Barco resident Rodney Kight. “They could visualize things that most people can’t. They built beautiful boats, by hand, without modern tools.”

As they always do, modern times crept in to Currituck. Watermen and sportsmen began to prefer the easy maintenance of a fiberglass boat. The native Currituck boat builders passed away. The old wooden boats, much as they were loved, were slowly relegated to side yards and forgotten on creek banks. Not able to withstand the elements without constant attention and maintenance, the juniper hulls were rotting and slowly being overtaken by vines and foliage.

Seeing that old way of life deteriorating, two lifelong Currituck residents decided to do something.

In the 1980s Travis Morris and Wilson Snowden began collecting the vintage vessels. Over the years they collected about 25 of them, storing them in horse stables, in sheds and the ground in their yards when they ran out of other places.

“Nobody is coming along to take up the art,” Snowden once said in an interview. “The wooden boat is hard to get out of your mind. I have a real appreciation for what the builders did. It’s a real craft.”

The two men, with the help of Snowden’s wife, Barbara Snowden, helped document Currituck-built vessels in the Library of Congress and on the North Carolina Historic Vessel Registry, and in 2008 they were given the Award of Merit from the American Association for State and Local History for their efforts to preserve the workboats of Currituck Sound. They donated some of the craft and seed money to Whalehead Preservation Trust, the organization that worked to preserve the Whalehead Club, to start a program to preserve some of the old boats. The trust displayed the boats in boat sheds around Corolla village, but Morris and Snowden hoped for more. It was their wish to one day see the boats restored and preserved in an indoor museum.

“If you don’t have a building to put them in, restoring them is a waste of time,” Morris once told an Outer Banks Voice reporter. “They’ll melt like butter in the sun.”

When the Currituck County Board of Commissioners disbanded the Whalehead Preservation Trust in 2015, they had the foresight to make a plan for the historic boats. The county established the Historic Boat Committee, appointing seven members to study the possibilities of interpreting the boats and building a museum to house them. The committee advised the county to restore some of the boats, and the county paid for the restoration of three. Another shed in Historic Corolla Park was built to temporarily shelter more of the boats where people could see them.

And now, after many years of planning, the Currituck Boat Museum is finally coming to fruition. Currituck County will break ground on the Currituck Boat Museum in Corolla in 2019. The museum will display 12 historic boats and tell the story of the builders and the history of Currituck through modern, interactive displays. The building, with an architectural design that complements Outer Banks Center for Wildlife Education, will be set in Historic Corolla Park on a site between Currituck Beach Lighthouse and the Whalehead Boat House. Paid for with occupancy taxes from vacation rentals and hotel stays, the museum also will house kid-friendly exhibits, a map of the old hunt clubs, public restrooms and a community classroom space.

There will be eight boats in the main area along with four more boats in an attached boat shed. All the boats going into the museum are in good shape or have been restored, except for possibly one that will show how the wooden boats deteriorate if they are not protected.

“These boats are an integral part of our history,” says Kight, who is chairman of the Historic Boat Committee. “If we don’t preserve our history, Currituck County will be just like any other place.”

Despite the fact that the boat builders and most of the people who used the boats lived on the mainland, the advisory board and commissioners chose Corolla as the location for the museum so that more people would see it. “You can’t put it on a back road in Currituck,” says Carl Ross, another committee member. “This way, people will see it and learn about Currituck’s rich boating history.”

Ross worked as a hunting and fishing guide in Currituck County for 45 years and was the superintendent of the Currituck Shooting Club for many of those years. He used some of the old wooden boats during his career and even built a few himself, so he has a soft spot in his heart for seeing them preserved.

Ross and Kight hope the museum will help people appreciate Currituck as more than just a tourist destination. “This place has tremendous history,” Kight says. “These boats and the people who built and ran them were rugged individuals. They had to be. They were outside, and that’s the way they made their living. Because of them and their foresight we learned to take care of our resources, and it’s a pretty good place to live.”

Sadly, Morris passed away in 2017, before the museum plan was finalized, but his appreciation of the boats was integral in bringing the museum to fruition. He knew that each boat had a story, and his work to preserve those stories will be incorporated into the exhibits. Morris was the author of numerous books about hunting and fishing heritage in Currituck County, and one of his books, written in 2014, was Hand-Crafted Boats of Old Currituck: Fishing & Boating on the Carolina Coast.

The vessels on display will represent a good cross-section of boat types, from sailboats to fishing boats to tunnel skiffs. The museum will include two fully restored examples of the North Carolina State Boat, the shad boat. Both were built on Roanoke Island but were used in Currituck Sound.

One of the vessels is a concave tunnel, 21-foot-long gas boat built by renowned local builder Pat O’Neal. The boat was commissioned by Earl Slick, owner of Pine Island and Narrows Island hunt clubs. The tunnel made the boat ideal for running in the shallow waters of Currituck Sound. Another one of the boats that will be on display is known as the Game Warden’s Boat. Local builder Blanton Saunders built the 17-foot boat for the State of North Carolina. Game Warden Howard Forbes Jr. used it as part of his job for such a long time that the state gave it to him when he retired.

Collectively, the boats are part of the storied history of Currituck and an example of the fortitude and creativity of its people. When it’s open next year, the museum will help them live longer in our memories.

Molly Harrison is managing editor at OneBoat, publisher of OuterBanksThisWeek.com. She moved to Nags Head in 1994 and since then has made her living writing articles and creating publications about the people, places and culture of the Outer Banks.

Molly Harrison is managing editor at OneBoat, publisher of OuterBanksThisWeek.com. She moved to Nags Head in 1994 and since then has made her living writing articles and creating publications about the people, places and culture of the Outer Banks.