Safe Havens from Slavery on the Outer Banks

If you’ve spent even a little time on the Outer Banks, you’ve heard about the trials of the early English colonies and the Lost Colony, the origins of the Spanish mustangs, the success of the Wright brothers’ 1903 flight and maybe even the harrowing life-saving efforts in the Graveyard of the Atlantic. But the Outer Banks has so many more fascinating stories that are not part of the collective awareness, stories that are tucked between book covers but infrequently vocalized.

For instance, many people don’t know the roles Hatteras and Roanoke islands played in helping North Carolina’s slaves find freedom during and following the Civil War. The state’s first protected safe haven for fugitive slaves was on Hatteras Island, and its first official colony for helping emancipated slaves establish a new life was on Roanoke Island.

Since there are no buildings or artifacts left from that time, it’s taken the work of many people to make sure that this history is remembered. They have written books, erected monuments, created museum exhibits, printed pamphlets and told the stories out loud. One of those people is Virginia Simmons Tillett, whose family has lived on Roanoke Island since before the Civil War. She wants people to know and remember that Dare County was founded by both blacks and whites. “I want the young folks to know about the history and contributions of the black race in Dare County,” she says.

To tell this story, we’re going to start with the Civil War on Hatteras and Roanoke islands.

At the beginning of the Civil War in April 1861, the people who lived on the islands here led simple lives and had little contact with the outside world. Slavery did exist – out of Roanoke Island’s 590 people in 1860, 171 of them were slaves – but slavery was less common on the other islands. The start of the Civil War had little impact on the islanders at first, and their intent was to remain neutral in the fight.

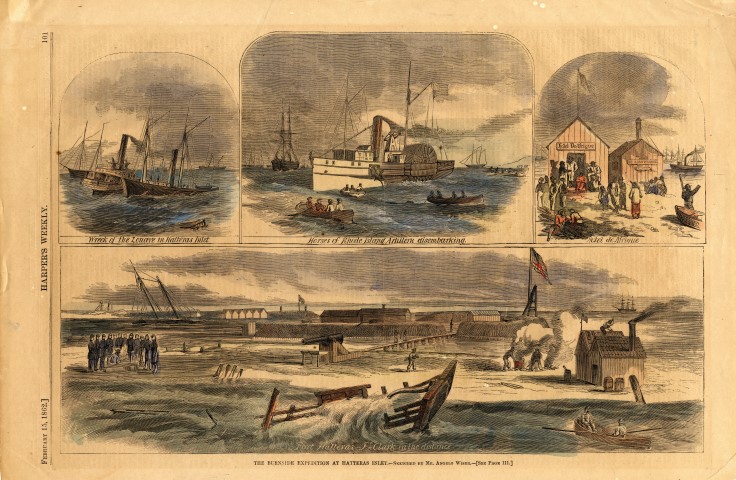

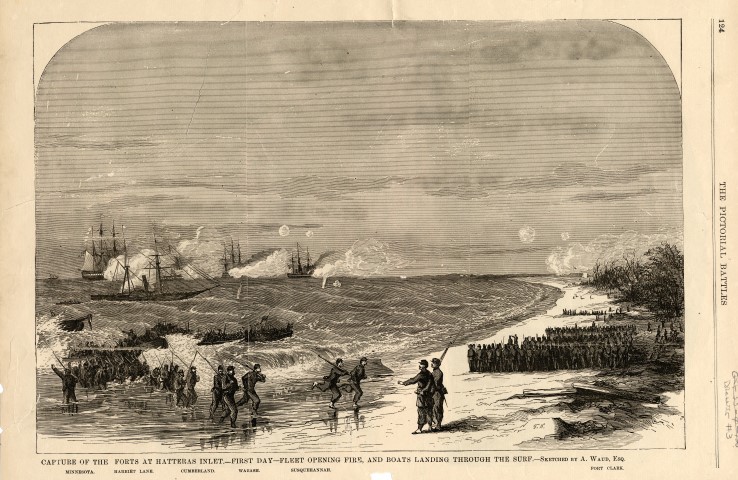

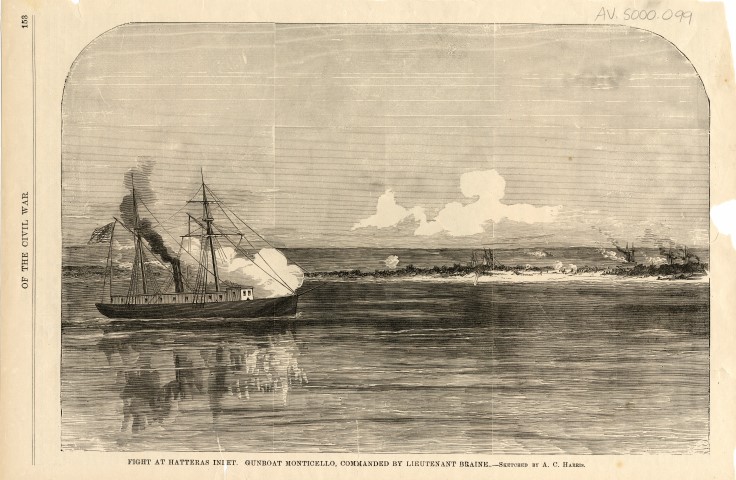

But by June of 1861, the Civil War came to Hatteras Island in the form of Confederate soldiers in the 7th North Carolina Troops. Their goal was to protect Hatteras Inlet, an important deep-water passageway to the Confederate supply route on the Pamlico and Albemarle sounds. With the help of slave labor, the Confederates built two forts of sand, brush and sod. Fort Hatteras, the larger, was right alongside the inlet, and Fort Clark was built less than a mile to the northeast.

It wasn’t long until the Union followed. In two days of battle on August 28 and 29, 1861, the Union easily overtook forts Hatteras and Clark and shipped the Confederates off to prison. As in other areas where the Union gained control of Confederate territories across the South, slaves from around the region fled to the newly established Union camps for protection.

So many slaves were arriving at Fort Hatteras that General John Wool sent a letter to the U.S. Secretary of War on September 18, 1861, “Tell me what I am to do with the negro slaves that are almost arriving daily at this post.”

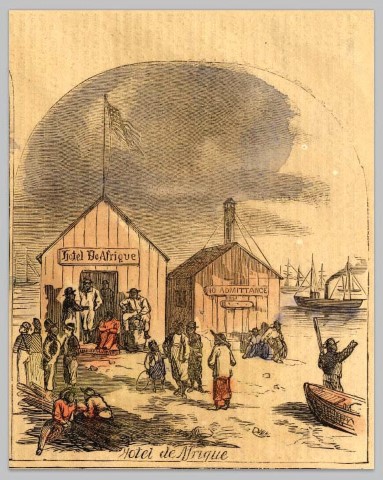

The Union troops transformed a Confederate-built building near Fort Hatteras into a barracks for the fleeing slaves. They gave them food and lodging in exchange for help building Union fortifications and loading ships. Since many of the fugitive slaves were expert watermen, they also helped Union soldiers with navigating the local waters. The barracks, or as Civil War artist Edwin Graves Champney referred to it, a shanty, became known as Hotel D’Afrique, and it was the first safe haven for fleeing slaves in North Carolina.

The Battle of Hatteras Inlet was a significant Union victory, and for a while the world’s eyes were on Hatteras Island. The New York Times reported from Hatteras in January of 1862. The article reported, “Capt. Clark has erected a very commodious wooden house on the beach, for the use of the fugitives who have recently arrived from Roanoke Island. It is christened ‘Hotel d’Afrique.’ These contrabands are very happy in their new quarters… They evidently left Roanoke Island not only for their health, but also with a view of improving their condition in life.” The article tells of Franklin Tillett, an old man from Roanoke Island, who arrived in a boat with 15 of his household, old and young, women and children included. They were very happy to hear that Congress forbade, under severe penalties, any Union officer from returning slaves to bondage. However, the article also referred to the hotel as more of a labor camp and not a comfortable place of living and mentioned that the black workers notched sticks for every day they worked to keep track of their meager pay, which often was paid in arrears.

In February 1862 Harper’s Weekly ran an image of the Hotel D’Afrique building after it had been moved from Fort Hatteras closer to Fort Clark. The original barracks was next to the inlet and flooded frequently, so in 1862 it was moved to higher ground on the soundside.

Meanwhile, the war had moved northward on the Outer Banks. The Union had its sights on controlling Roanoke Island, home of four Confederate forts. Fought on February 7 and 8, 1862, the Battle of Roanoke Island ended with the Union in control of Roanoke Island.

At the time of the battle there were more than 200 blacks working at the Confederate camp on the island. After the battle, it’s said these workers were singing and dancing upon learning that they were now free and could remain on the island, although some left to try to free their relatives who were living elsewhere. Slaves still on Roanoke Island and fugitive slaves from around northeastern North Carolina escaped their captors, under the cover of night on foot and in stolen boats, and sought refuge at the Union camp. And, again, the most pressing issue for the Union soldiers was where to house the incoming people.

By March, the Union began organizing the situation. Brig. General Ambrose Burnside appointed a superintendent of the “contraband camp,” and the fugitive slaves were provided with food and basic needs. They were employed to build Fort Burnside and docks around Roanoke Island. Over the coming months, more than 1,000 escaped slaves, some of them from Hotel D’Afrique, gathered on Roanoke Island. The men worked for the military, constructing Fort Burnside, docks and other buildings, and the women washed and cooked for the soldiers.

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing millions of slaves in Confederate territory. More than 100 black Roanoke Islanders voluntarily enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops, including Richard Etheridge, a 21-year-old former slave who had learned to read and write, despite laws against slave education.

The Roanoke Island contraband camp was later officially designated as a colony and named the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony. It’s not known precisely where the colony was located, but based on the documentation available, it is believed the colony was on the north end of the island, partially on and north of the current airport. The colony was organized into avenues and cross streets, and plots were assigned to black settlers. The colonists built simple homes and planted gardens and built schools, churches, a hospital, stores and other enterprises. By January of 1864 there were more than 2,700 black residents on Roanoke Island, and the overall island population was 3,500, more than six times the number prior to the war.

Down on Hatteras, Hotel D’Afrique and its surrounding buildings were still in operation as well. By 1864 there were as many as 12 wooden barracks on the soundside near Fort Clark. A U.S. Army Corps of Engineers map from March of 1864 labels the buildings as “Negro Camp.”

Little is known about daily life at Hotel D’Afrique, but reports describe relations between the former slaves and soldiers as positive for the most part, despite a few hostile incidents. Not all was idyllic at the Freedmen’s Colony. Many of the men were enlisted with the Union army, which left the women and elderly to build and take care of the colony, and the men’s compensation and wages did not always come through. There were reports of corruption and abuse at the colony, which prompted Etheridge to write a letter of protest to the Freedmen’s Bureau.

While the end of the war in April of 1865 was good news, bad news followed for the Freedmen colonists when President Andrew Johnson declared that all land should be returned to the original owners who held the title. The Freedmen’s Bureau controlled 1,800 aces on Roanoke Island, and 1,114 acres had been occupied for the use of the freedmen, many of whom believed the land they were living on was theirs to keep. Blacks were encouraged to leave (partially by making life difficult for them with reduced rations), and steamships arrived at Roanoke Island, offering rides to inland counties and to cities in the North. Most of the colonists eventually left or were forced to leave, but some, especially those who were on the island before the war, refused to leave. Etheridge had returned to Roanoke Island after the war and helped thwart the effort to remove black natives from the island. While the former white landowners were petitioning to have their land returned and some of the blacks were trying to find a way to stay, a smaller version of the colony remained, though conditions were greatly deteriorating and rations were greatly reduced. By summer 1867, the colony was disbanded.

In 1868, 11 former Freedmen colonists scraped together $500 and bought 200 acres on Roanoke Island. They split it into 11 parcels and called the area California. It’s said Roanoke Island was a better place for black residents than some other areas in the South because, for the most part, relations between blacks and whites were decent and plentiful work was available in fishing and fowling. Etheridge resumed commercial fishing with his former master, started a family and became a community leader; he later became the first keeper of the nation’s first all-black U.S. Life-Saving Service crew at the Pea Island station (and today has a bridge named after him and a statue commemorating him on Sir Walter Raleigh Street in Manteo). Most of Virginia Tillett’s ancestors headed north, but her grandmother, Lila Ashby Simmons, stayed and continued her life on Roanoke Island, running a boarding house and cleaning geese for hunters. By 1900 there were 300 black residents living on the island, many of them on land they owned. Their lives were not perfect, but they were free and an integral part of the island community.

All vestiges of the Freedmen’s Colony slowly vanished, the barracks and the houses, the churches, the graves. The original Haven Creek Baptist Church, built in 1865 and attended by members of the Freedmen’s Colony, is in a different building and location today. Slowly, people stopped talking about the Freedmen’s Colony and Hotel D’Afrique. Tillett remembers that her grandmother didn’t call the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony by name, instead calling it “the settlement.” As a teenager Tillett says she was too young to ask about the settlement and what it was, and by the time she was interested it was too late to ask.

Tillett and others started piecing the history together in 1981, when Manteo Mayor John F. Wilson, IV named young Patricia Click as the town’s historian-in-residence intern and gave her the assignment of researching the former slave colony on the island. Click met with Tillett and others in the black community and asked them about their ancestors who had lived in the Freedmen’s Colony, but no one knew much. As Tillett went around with Click to talk with colony descendants, she became more interested in the story. She and some of her island neighbors, including Dellerva Collins and Arvilla Tillett Bowser, conducted more research to learn about their ancestors. “I was interested to find out what they went through so I could see where they got their resourcefulness,” Tillett says.

Two decades later Dr. Patricia Click wrote Time Full of Trial: The Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony, 1862 to 1867, incorporating a wealth of information into the first book about the colony. Bowser later wrote a book called Roanoke Island: The Forgotten Colony about the Freedmen’s Colony descendants and their families, churches, schools and community on Roanoke Island, up to contemporary times.

Hotel D’Afrique remained a buried piece of history until almost 2013. The camp was mentioned in a few texts, including Drew Pullen’s 2001 book The Civil War on Hatteras Island North Carolina: A Pictorial History, but for the most part no one remembered it or talked about it, and the land where it was located had long since washed away.

It’s hard to tell a story with no location, so people began to make efforts to mark them. In 2001 Collins, Tillett, Mel Covey and others in the Dare County Heritage Trail citizen committee erected a marble monument for the Freedmen’s Colony at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. In 2004 the monument was added to the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, the first such site in North Carolina.

It wasn’t until a decade later that a National Park Service staff member, Doug Stover, brought up the idea of adding a historic marker for Hotel D’Afrique. The marker was established in 2012 on a site near the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras. It was added to the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom in 2013.

Like many other pieces of Outer Banks history, Hotel D’Afrique and the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony are stories of national significance. Yet, they aren’t told in schools and history books, and that’s what makes them so much more important to tell and remember. And thanks to a handful of people, the stories live on.

Timeline

Pre-Civil War: Escaped slaves hide in the Dismal Swamp in what was possibly the largest hidden fugitive colony in the United States

April 1861: Start of the Civil War

May 1861: N.C. one of last states to secede from the Union

June 1861: Confederate troops arrive on Hatteras Island and start construction of forts Hatteras and Clark, plus several shacks and barracks

August 28 & 29, 1861: Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries. Union gains control of Hatteras

Fall 1861: Union establishes Hotel D'Afrique, a safe haven for fugitive slaves near Hatteras Inlet

February 7 & 8, 1862: Battle of Roanoke Island Union gains control of Roanoke Island

April 1862: Roanoke Island “contraband camp” numbered 250 freed slaves

January 1, 1863: Lincoln issues Emancipation Proclamation

April 1863: Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony established

January 1864: More than 2,700 black residents living on Roanoke Island

1867: Freedmen’s Colony disbanded

1872: Last record of Hotel D’Afrique building still standing

1997: National Park Service establishes National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom to identify sites

2001: Freedmen’s Colony monument established at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site Visitor Center

2004: Freedmen’s Colony monument added to National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom

2012: Historic marker for Hotel D’Afrique established in Hatteras village

July 31, 2013: Hotel D’Afrique marker added to National Underground RailroadNetwork to Freedom

Places to Visit

Look around and you’ll find reminders of the Civil War era and the Freedmen’s Colony on Roanoke and Hatteras islands. Here are a few places to visit:

Lindsay Warren Visitor Center at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony Monument and exhibit about the Freedmen’s Colony

North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island

Gravesites of Richard Etheridge and family. Across the street from the aquarium on Airport Road is a memorial marker for all the slaves who lived in the area

Freedmen’s Colony Roadside Marker

Found on U.S. Highway 64 near Airport Road

Free Grace Church Cemetery and Haven Creek Church Cemetery on Roanoke Island

Burial grounds that contain gravesites of Freedmen’s Colony descendants

Island Farm

A realistic example of 1850s life on Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island Festival Park

Exhibit on the Freedmen’s Colony in the Adventure Museum

Cartwright Park/Collins Park

A monument of Richard Etheridge on Sir Walter Raleigh Street in Manteo

Hotel D’Afrique State Historical Marker

Near the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras

All images courtesy of Outer Banks History Center, Discreet Audio/Visual Items

Sources: Time Full of Trial: The Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony, 1862-1867 by Patricia Click; The Civil War on Hatteras Island North Carolina:

A Pictorial Tour by Drew Pullen; and The Civil War on Roanoke Island North Carolina: A Pictorial Tour by Drew Pullen

Molly Harrison is managing editor at OneBoat, publisher of OuterBanksThisWeek.com. She moved to Nags Head in 1994 and since then has made her living writing articles and creating publications about the people, places and culture of the Outer Banks.

Molly Harrison is managing editor at OneBoat, publisher of OuterBanksThisWeek.com. She moved to Nags Head in 1994 and since then has made her living writing articles and creating publications about the people, places and culture of the Outer Banks.