Volumes of history are written under the waters that surround the Outer Banks, but none of it was written on purpose. Most all of it was borne of a tragedy in the form of a shipwreck.

When most of us think of shipwrecks, here in the Graveyard of the Atlantic where so many ships have gone down, we imagine an ocean floor littered with the remains of vessels both great and small. While this is certainly true, since an educated guess is that many thousands of ships, some estimates as high as 6,000, have been lost in surrounding waters, the location of these wrecks is not limited to the ocean, as we so often think. Many hundreds of ships went down in the sounds and rivers and near shore surrounding us — in the brown water as opposed to the deep blue water.

Marine archeologists working out of the UNC Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), located in Skyco on Roanoke Island, an inter-university research facility, are studying these wrecks and adding to our history lessons with each discovery they make. And, since so many of the wrecks in these waters were a casualty of war, both Civil and WWII, each new find adds a clarifying chapter to the details we know from written accounts.

Nathan Richards, Maritime Heritage Program Head at CSI, and an Associate Professor in East Carolina University’s Program in Maritime Studies (one of only three such programs in the United States), collaborates with a team of new ECU graduate students each year in researching wrecks. Notice that the term is researching, not just searching. He explains that when they search for a wreck, perhaps the factor most influential to successfully finding it is the discipline of stages before they ever get onto the water. The first question they ask themselves is why they are looking for that specific wreck in the first place. What do they already know about the history of the vessel? Was it involved in a documented war battle? Have other artifacts such as cannons, cannon balls, projectiles or metal pieces indicating a ship been seen or found nearby? Is there a definable debris field that would point to a logical location?

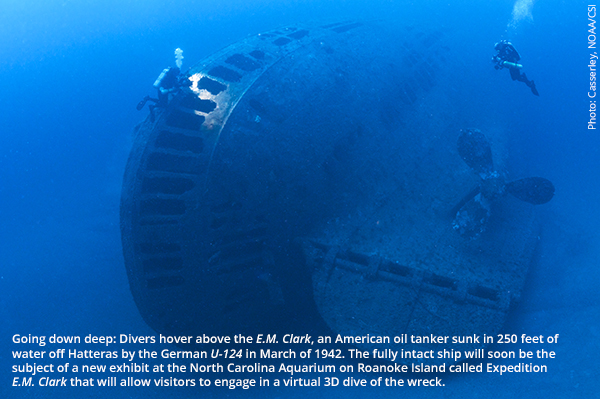

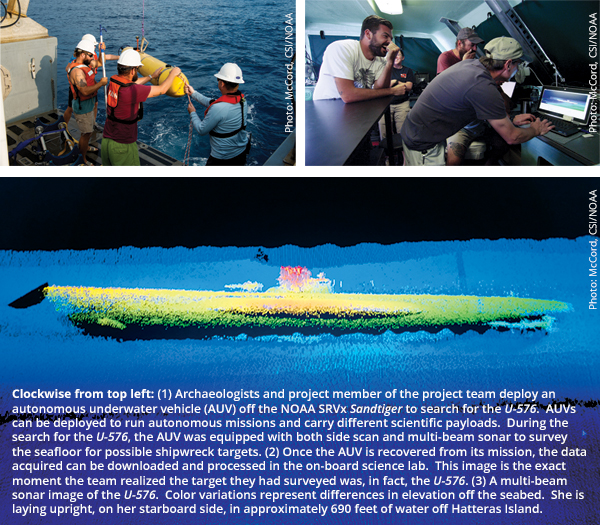

Only after these and many other questions have been answered does the team load their sidescan sonars and magnetometers onto the boat to begin the grid search pattern in the water. Each piece of equipment shows them a different view from which they’re able to build images that either confirm or deny a find.

One recent find from the summer of 2014 is the German U-576 and the Nicaraguan freighter Bluefields off the coast of Ocracoke Island. The story of their fatal encounter is intriguing when the context is understood, and that context being the significance of this conflict in bringing about Germany’s loss of control of the strategic Atlantic waters. In a research design titled Battle of the Atlantic Expedition 2011, The Battle of Convoy KS-520, Richards, ECU geography professor Tom Allen, graduate student John Bright and NOAA personnel Joe Hoyt and John Wagner explain this context and provide a written account of the encounter.

A synopsis of their research goes like this: In the months leading up to the loss of both ships, German U-boats had been sinking American merchant vessels off the East Coast at an alarming rate, with nearly 200 sunk in the first four months of 1942. Slowly, however, the Allied command began to respond effectively with convoys that included Coast Guard and naval escort ships protecting the merchant supply ships, air escorts and the mining of certain strategic harbors.

Bluefields was part of the KS-520 convoy that left port near Hampton Roads, Virginia, in the early morning of July 14, 1942 heading south. Included were 19 ships, five of which were escort ships. The trip was without incident that day, and by 7 a.m. the next morning, the convoy had rounded Cape Hatteras. But at 4 p.m. one of the escorts, USCG Triton, picked up an enemy contact and bombed, unsuccessfully. Knowing this action would draw attention from any other Axis submarines that might be in the area, the other four escort ships stepped up their efforts to detect signs of them on the horizon. Such vigilance failed, however, as only a few minutes later the lead ship in the second column of ships, Chilore, was torpedoed twice in a matter of a few minutes. Immediately after, the J.A. Mowinckel, was devastated by another torpedo.

At this point, the convoy started breaking apart to try to scatter the deadly efforts of the attacking U-boat. As formation broke, Bluefields was hit and began rapidly sinking. For reasons unknown, the U-576 then popped to the surface, and in quick succession it was attacked by Allied escorts, bombed from the air and depth charged.

The sinking of the U-576 and the naval action of the KS-520 convoy signaled a change in the balance of power in WWII. As Richards and his team explain, “Though only a single naval action, KS-520, in fact, marks a shift in strategic initiative off America’s eastern seaboard. The significance of this shift would reverberate throughout the entire Atlantic. Once the Allies drove German U-boats from American waters, German hopes of dominating Atlantic seapower were lost.”

The detailed, 86-page report is an example of the depth of research conducted as part of the search for wrecks. And, indeed, less than two years after the research design, these two sunken ships were found during a research expedition lead by NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary.

Currently, the team is researching the Battle of Elizabeth City, a Civil War conflict that took place in the Pasquotank River on February 10, 1862, following the Battle of Roanoke Island a few days prior during which Union forces took control of the waters surrounding the island. The nearby Dismal Swamp Canal and Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal were vital transport lines for the Confederate forces, and the Union leaders understood that controlling these waterways would deal a serious blow. Of the eight Confederate ships, known as The Mosquito Fleet, six were either captured or sunk by the Union forces or intentionally burned by the Rebels. Fourteen Union ships mounted the attack, and none were lost in the battle.

Richards and his team explain that part of the intrigue of finding these ships, in addition to adding to our maritime knowledge of these wrecks, is uncovering more of our American history. As Richards say, “This is about America in the context of everyday life – not just about shipwreck icons such as the Titanic or Blackbeard’s Queen Anne’s Revenge. Many of these vessels used in the Civil War were merchant ships, pressed into service to run supplies. These ships connect directly back to us and the way local people were affected by war.”

While these brown water wrecks are easier to get to, they present research challenges due to the lack of visibility in the murky waters in which they rest. The blue water wrecks, by contrast, are lost in countless miles of ocean bottom and are typically much deeper than even the highly trained divers with the Maritime Heritage Program can reach. But CSI’s focus, along with that of their partner on many searches, NOAA, on these blue water wrecks and new technologies are making the outcomes of both scenarios better all the time. Over the past six years, more than 300 square miles of ocean floor just off the coast of the Outer Banks have been surveyed using an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle, and more than 50 WWII ships have been documented during NOAA-led missions. Every year, these scientists are helping us connect the records we have of ships going down with the actual archaeological discoveries.

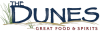

Helping us connect even more will be a new exhibit at the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island, coming this Spring, called Expedition E.M. Clark that will let visitors engage in a virtual 3D dive of the wreck. The ship, sunk by a German U-boat in March 1942, rests in 250 feet of water 22 miles off the coast of Cape Hatteras and is fully intact. This project, as with many at CSI, is a partnership of researchers from NOAA, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and East Carolina University.

The Outer Banks has long been known as a key site for wreck divers, but with the ever-increasing discoveries of the Maritime Heritage Program researchers, these mysteries of the deep are revealing themselves and the secrets they hold.

UNC-Coastal Studies Institute: An Introduction to Our State’s Dynamic Collaboration for Coastal Research and Education

Driving west from Nags Head toward Roanoke Island you’ll cross Washington Baum Bridge, a graceful edifice gently arching over the Roanoke Sound separating Nags Head from Roanoke Island. Near the top of the bridge an amazing panorama opens before you, an incredible 360-degree view encompassing an island, four sounds, the mainland in the distance ahead of you and a beach and the Atlantic Ocean in the rearview mirror. In the midst of all this natural grandeur is one man-made object sure to catch your eye — a large shiny, glassed modernist structure rising from the surrounding marsh on the far side of Roanoke Island like a spaceship from the future. Congratulations, fellow earthling. You’ve just had your first introduction to the UNC Coastal Studies Institute.

The Coastal Studies Institute (CSI) is an inter-university research institute located in the small community of Skyco, just south of the midway point of Roanoke Island. Conceived to address a research gap regarding North Carolina’s coastal areas, examine pressing issues related to the region’s development and the impact on its natural resources, the Coastal Studies Institute is the product of a partnership between the UNC Office of the President, East Carolina University, Dare County and its citizens and other universities of the UNC system.

Established as an academic program in 2002, the Institute has recently completed the first phase of campus construction, and the magnificent structure drivers see from the top of the Washington Baum Bridge is CSI’s new Research and Education Building. Also newly completed is the campus’ Marine Operations Building. From these facilities the Institute conducts research, offers educational opportunities and community outreach programs to northeastern North Carolina and facilitates communication among those concerned with the history, culture and environmental conditions of North Carolina’s maritime counties.

In addition to providing unbiased scientific information to decision makers, resource managers and the public, CSI’s research focuses on five main areas: Estuarine Ecology and Human Health, Coastal Engineering and Ocean Energy, Public Policy and Coastal Sustainability, Maritime Heritage, and Coastal Processes. This research draws on the resources of the entire region and encompasses all of the mid-Atlantic and southeastern coast of the United States.

Northeastern North Carolina is home to a unique array of ecosystems and a rich and varied culture and history. The recent influx of people to this previously sparsely populated region brings both positive economic and negative environmental impacts. The importance of the area’s ecosystems calls for a sustained, intensive and collaborative consideration of water quality, fisheries, habitats, tourism and other human interaction with the environment. The thousands of shipwrecks and rich maritime history of the Outer Banks also provide a wealth of opportunity for scholarly pursuit.

850 North Carolina 345, Wanchese, NC 27981 • (252) 475-5400 • csi.northcarolina.edu

Beth Storie first came to the Outer Banks for the summer of 1976. She fell in love with the area and returned for good three years later. She and her husband published the national guidebook series, The Insiders' Guides, for more than 20 years and now are building OneBoat guides into another national brand. After spending time in many dozens of cities around the country, she absolutely believes that her hometown of Manteo is the best place on earth, especially when her two children, six cats and one dog are there too.

Beth Storie first came to the Outer Banks for the summer of 1976. She fell in love with the area and returned for good three years later. She and her husband published the national guidebook series, The Insiders' Guides, for more than 20 years and now are building OneBoat guides into another national brand. After spending time in many dozens of cities around the country, she absolutely believes that her hometown of Manteo is the best place on earth, especially when her two children, six cats and one dog are there too.