A close call for a shrimping vessel and a dramatic rescue from the Coast Guard occurred on the beach in Southern Shores this week, bringing a reminder of the dangerous conditions boaters and fishermen often face off the Outer Banks.

The 78-foot shrimping vessel, Bald Eagle II, communicated to the U.S. Coast Guard at 7:30 a.m. on Tuesday, December 7, that it was disabled and drifting toward shore, despite having dropped an anchor in hopes of staying out of the breakers. A helicopter from Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City was dispatched to the scene, and all four people on board were airlifted to safety. The rescue operation made for fascinating viewing near the beach access at E. Dogwood Trail in Southern Shores. The boat is being removed from the shoreline, and meanwhile the story has received national coverage, with photos of the rescue all over the internet and in print around the country.

This photo and the one above are from this week's Bald Eagle II shipwreck on the beach in Southern Shores.

Long ago, shipwrecks were much more common on the Outer Banks, and they most often made the national news. People back then, as now, are fascinated by what happens at the confluence of land and sea. Some estimates say there are 3,000 shipwrecks off the Outer Banks, caused by war, weather and shoals. Thanks to GPS and other technological advances, shipwrecks are much less common here today than they used to be. Boats still wash ashore from time to time – as was the case when the scallop boat Ocean Pursuit ran ashore near Oregon Inlet in 2020, but it's a rare occurrence. However, that doesn't mean the Coast Guard is not busy. On the Outer Banks we frequently hear about Coast Guard crews rescuing people off disabled boats or rescuing injured people from vessels, sometimes hundreds of miles offshore, sometimes in the tricky inlets and sometimes right within sight of the surf.

Despite the historic abundance of shipwrecks and deaths at sea, the Outer Banks did not have a formal life-saving service until 1874. Prior to then, residents of the Outer Banks assisted with shipwrecks as they could as Good Samaritans without any equipment or training. In 1848 the federal government established the United States Life-Saving Service in the Northeast to help save lives in shipwrecks, but the service did not come to the Outer Banks until 1874.

The first Outer Banks Life-Saving Service stations were at Jones Hill (Currituck Beach), Caffeys Inlet, Kitty Hawk, Nags Head, Oregon Inlet, Chicamacomico and Little Kinnakeet. The stations were manned from December to March.

Two back-to-back shipwrecks spurred the need for more stations on the Outer Banks. On November 24, 1877, the Huron encountered a heavy storm and ran aground offshore of Nags Head at 1:30 a.m. It was only 200 yards from shore, but darkness, heavy surf, strong currents and cold temperatures prevented the crewmembers from swimming to shore, and the nearby lifesaving station was closed until December. In all, 98 men drowned that night. A few months later, on January 31, 1878, the vessel Metropolis struck shoals 100 yards from the beach on the Currituck Banks, halfway between two Life-Saving Stations. By the time the wreck was spotted and efforts were underway, 85 people had died. The two wrecks prompted Congress to add more stations on the Outer Banks and extend the lifesaving season.

Later stations were added at Wash Woods, Pennys Hill, Poyners Hill, Paul Gamiel Hill, Kill Devil Hills, Bodie Island, New Inlet, Pea Island, Gull Shoal, Big Kinnakeet, Cape Hatteras, Creeds Hill, Durants, Hatteras Inlet, Ocracoke and Portsmouth Island, and the lifesaving season was gradually extended to last from August 1 to May 31. Each station housed a keeper and a crew of six. Crew members regularly patrolled the beaches, searching for shipwrecks, and the 29 Outer Banks stations saved thousands of lives.

There are hundreds of tales of Outer Banks shipwrecks and rescues, and here are a few of the more famous ones. The information for the stories recounted here is from Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic by James D. Charlet, who tells these stories and many in much more detail.

Ephraim Williams

December 22, 1884

The Ephraim Williams encountered Frying Pan Shoals near Wilmington during a storm, then drifted without control toward Cape Hatteras. Crews from the Durants, Creeds Hill and Cape Hatteras stations spotted the ship on December 21 in mountainous seas too rough for a surfboat rescue. They could not reach the ship, nor could they detect signs of life aboard, so all they could do was watch and wait. On December 22 the ship had drifted north and grounded on Diamond Shoals opposite Big Kinnakeet Station in Avon. Around 10:30 a.m. life-saving crews spotted the first sign of life: a flag raised on the ship. Crewmen from Cape Hatteras station rowed through five miles of breakers in a surfboat to reach the ship. They anchored nearby, threw a line to the ship and removed the nine-man crew to the surf boat one man at a time before rowing back five miles to shore with everyone alive. The crew of the Ephraim Williams had been experiencing shipwreck conditions for 90 hours, but they were safe.

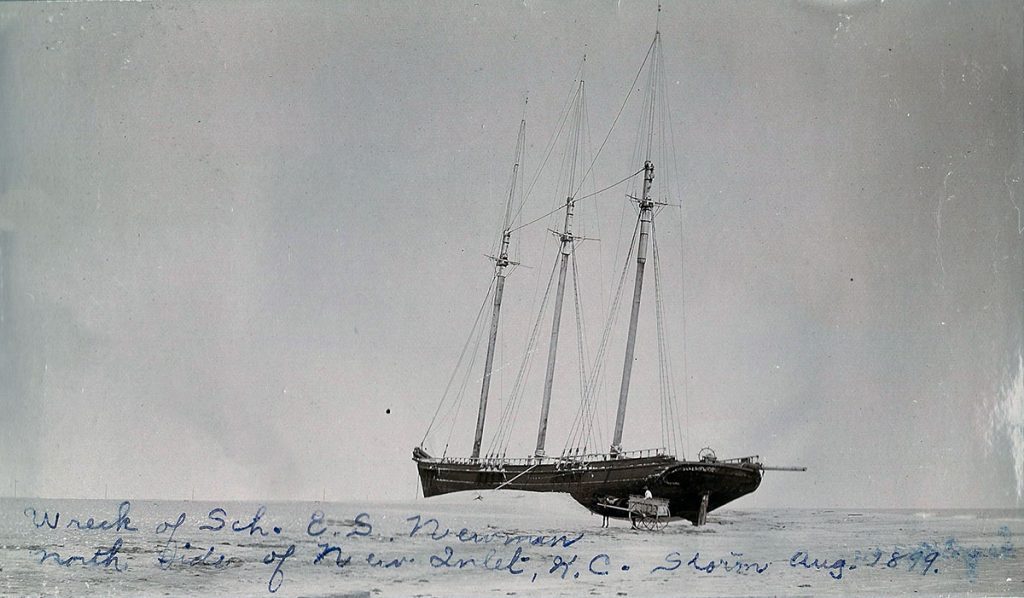

A photo from the wreck of the E. S. Newman

E. S. Newman

October 11, 1896

The E. S. Newman ran aground at night near the Pea Island Station during a hurricane with winds exceeding 100 mph. The ocean was too violent to launch the surfboat, and the beach was covered in overwash, so all the usual lifesaving tools were rendered useless. Keeper Richard Etheridge asked for two volunteers from his crew. His plan was to tie a rope around two men, with the end of the rope anchored by the remaining surfmen onshore. The two men would swim into the breakers to the ship. Surfman Theodore Meekins, who had originally spotted the ship on his beach patrol, was the first to volunteer. He and another crewman rescued the captain's three-year-old son first, then the captain's wife, then the six crew members one by one, until finally they brought the captain to shore at 1 a.m.

Priscilla

August 18, 1899

The Priscilla came ashore near the Gull Shoal Life-Saving Station just south of Salvo during the San Ciriacao Hurricane. The storm struck Hatteras Island on August 16 and stuck around for two days. Seven vessels were lost as total wrecks on the beach, and six more completely disappeared at sea. Surfman number 1 at the station, Rasmus Midgett, was on beach patrol at 4:30 a.m. on August 18 when he heard the cries of men aboard the shipwrecked Priscilla, which had been torn in two in the surf. Midgett faced the dilemma of riding more than an hour back to the station for help or to attempt the rescue by himself. He chose the latter. Somehow he instructed one person at a time to jump off the ship when he commanded and then swam out between the waves and retrieved the person, swimming them to shore. He did that seven times. For three people on board who were too injured to jump, he swam to the wreck and brought them back to shore one at a time.

Mirlo

August 16, 1918

Mirlo, a British tanker hauling gasoline up the N.C. coast, was hit by a torpedo from a German U-boat on August 16, 1918. The tanker was hit midship, and there were two initial explosions, which split the ship in two. The captain ordered the crew to abandon the ship to two lifeboats, which could hold 18 people each. The problem was that there were 51 men on board. One lifeboat got away from the burning ship safely. The other overloaded lifeboat capsized upon launch, spilling sailors into the sea. A third explosion spilled the Mirlo's entire cargo of gasoline into the sea, and the ocean surface raged with fire. On shore, the Chicamacomico Station was responding to the disaster with the help of the Gull Shoal Station. It took 30 minutes to launch the surfboat into the raging seas. The lifesaving crew, headed by Chicamacomico Captain Johnny Midgett, rowed out past the breakers, reached the lifeboat full of sailors and instructed them to row to shore but wait for the life-saving crews to help them to safety. The lifesaving crew in the surfboat rowed out five more miles to the ship, only to be blocked by a wall of fire. Through a miraculous break in the smoke and flames, the crew spotted the overturned lifeboat. The life-saving crew paddled through the opening in the flames and found six men coming out from underneath the capsized lifeboat and pulled them into the surfboat. The sailors pulled from the water alerted Captain Midgett that there were 19 other men spotted on the stern of the sinking ship at one point. These men had launched another small boat, which was overloaded by their weight and therefore impossible to row and was drifting, about to capsize. Captain Johnny and his crew, along with the six sailors they had pulled from the sea, rowed south away from the flames, searching for these survivors. Nine miles later they found the small boat with the 19 men. They took that boat in tow and rowed nine miles back against the wind, met the first lifeboat they had instructed to wait, and ferried the survivors to shore, one boatload at a time. In the six-and-a-half-hour rescue, 42 British sailors were saved.

The U.S. Life-Saving Service became the U.S. Coast Guard in 1915. On the Outer Banks today there are Coast Guard stations at Oregon Inlet and Hatteras Inlet, and there is a U.S. Coast Guard Air Station in nearby Elizabeth City. One of their nationally famous rescues occurred in 2012.

U.S. Coast Guard photo of HMS Bounty sinking off Cape Hatteras during Hurricane Sandy.

HMS Bounty

October 29, 2012

The 169-foot Bounty was built in 1960 for MGM for their 1962 film Mutiny on the Bounty. It was inspired by the 1790 ship of the same name. After the filming of the movie, the ship was a tourist attraction in Florida, then later donated to the Tall Ship Bounty Foundation and featured in several more movies and traveled the world. In the fall of 2012 as Hurricane Sandy threatened the East Coast, the Bounty's captain decided to put to sea, thinking the ship was safer at sea than at port. A volunteer crew signed on to go with the captain to sea. The 52-year-old wooden ship left Connecticut on the morning of October 25, and by 9 p.m. that night had signaled distress to the Coast Guard base in Wilmington, N.C., that they were taking on water. A Coast Guard Hercules airplane was launched from Air Station Elizabeth City to locate the Bounty. At 4:26 a.m. on October 26, the captain had ordered his crew to abandon the ship into life rafts. The Hercules aircraft found the rafts and kept watch on the sailors, and at 5:30 a.m. a Coast Guard Base Air Station Elizabeth City rescue helicopter began rescue operations in heavy rain and powerful winds. Flying low at 300 feet, they spotted one survivor in the water, alone. It took several attempts to get the rescue basket to the person, but the person was saved. Then the station's rescue swimmer began rescuing survivors from a life raft in waves cresting at 30 feet. The helicopter and rescue swimmer were able to rescue people from the second life raft as well. They evacuated 14 of the 16 crewmen from life rafts. A 15th crewmember was found deceased seven nautical miles from the wreck site, and the captain's body was never found, despite more than 90 hours of searching.

Charlet's book and many others about Outer Banks shipwrecks are available in local bookstores and make great Christmas presents!

Molly Harrison is managing editor at OneBoat, publisher of OuterBanksThisWeek.com. She moved to Nags Head in 1994 and since then has made her living writing articles and creating publications about the people, places and culture of the Outer Banks.

Molly Harrison is managing editor at OneBoat, publisher of OuterBanksThisWeek.com. She moved to Nags Head in 1994 and since then has made her living writing articles and creating publications about the people, places and culture of the Outer Banks.